Kai H. Kayser, MBA, MPhil

Portugal. Jan 3, 2026.

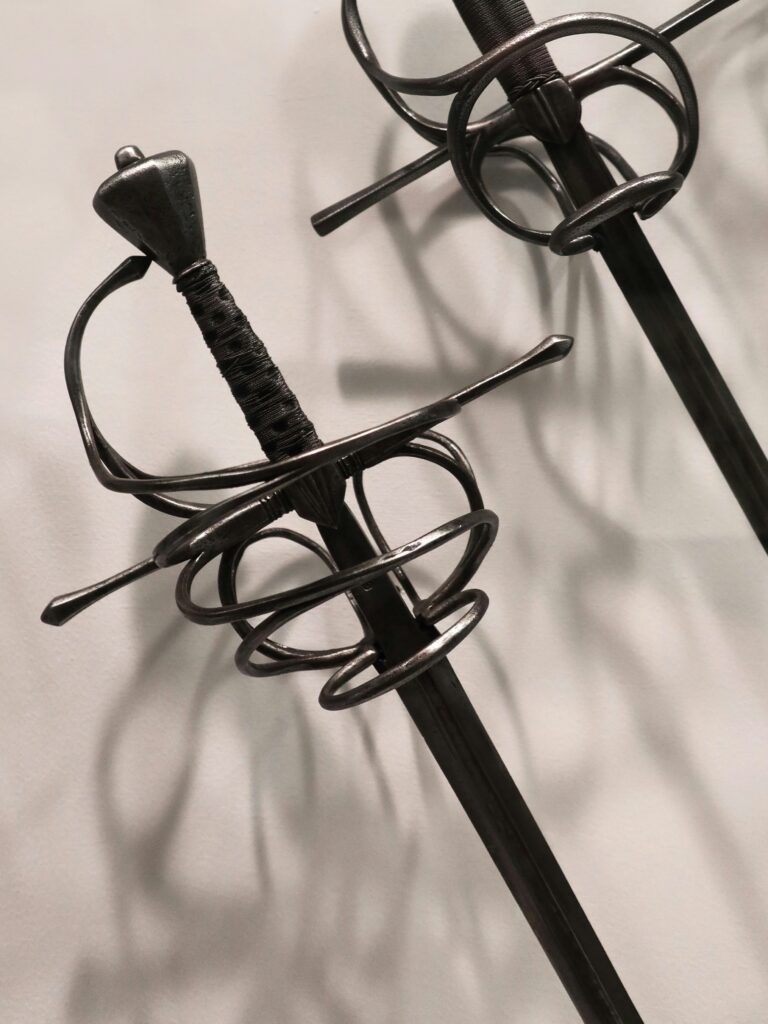

In Portugal and Spain we can observe many different swords, metaphorically, as the double-edged sword, the one hanging over our heads on a thin thread or the hidden one. In the 1960s, both Portugal and Spain were under right-wing dictatorships and started their new and well-intended but ill-informed industrial policies causing one of the world’s worst rural exoduses. Portugal’s Salazar made that even worse by engaging in colonial wars, completely ruining whatever economic success he had achieved until then. So, yes, as much as we don’t like to admit it, economically both Salazar and Franco had their moments, and private property and home ownership were strong, public debt and inflation low and both countries enjoyed rather impressive safety. Unemployment numbers were also not too bad, and yet, the lack of freedom of speech and expression was a major issue, which is why not too many Iberian citizens wish back either one and Salazar even less than Franco. As a matter of fact, Portugal was so thoroughly fed up with nationalism and right-wing ideologies, that for the last 50 years, since 1974, social democrats and socialists dominated in Portuguese elections. In Spain, where Franco’s regime ended at nearly the same time, 1975, and Spain’s democracy started officially in 1978, with the same miserable results: In both countries public debt rose exponentially, and so did the tax burden and inflation. Home ownership faltered amid speculation and corruption, exploding material and labor costs and their shortages. Real estate, the backbone of societal economic well-being became problematic but of course the corrupt politicians that aggravated the situation with their shortsighted and sure to fail policies soon blamed “corporate greed”, “tourism” and “rich foreigners coming in buying up all good real estate”. While that may seem just another essay blaming socialism (which it indeed does), it is important to notice that it also points out the just as incompetent policies of the conservative parties, who only sounded good, but ultimately delivered the same mistakes and schemes. After 50 years of corruption and myopic errors, of ever increasing costs and taxes, of ever worse impoverishing the citizens while redistributing their wealth in the most counterproductive ways, all over Europe new “right wing” parties formed: Chega in Portugal and Vox in Spain. The established powers and parties, media and educational institutes went on an indoctrination crusade against that “threat of our democracy”. Hence, this essay! We will attempt to show the true culprits for Iberia’s grave issues, impoverishment and deindustrialization, while showing that the forming opposition is not offering exactly promising remedies. As a third part, this essay shows what empirically did work and what is most likely to be Iberia’s best solution – aparactonomy, or the “stateless nation” (Kayser, 2025). First, let’s clarify the difference between patriotism and nationalism, then see their empirical advantages and disadvantages, and do so from an Austrian economist perspective, where we define societal improvement and well being as consequential to the creation of wealth. While many organizations argue that wealth creates inequality, injustice and environmental problems, we argue the exact opposite, embracing inequality as something beneficial, while we show wealth as historically the best way to establish justice and peace, solving problems like environmental issues that all stem from central planning, cronyism and statist corruption.

Clarifying Patriotism and Nationalism: Definitions and Distinctions

Patriotism and nationalism, though often conflated in public discourse, represent distinct orientations toward one’s country, its people, and its role in the world. Patriotism is fundamentally a sentimental attachment to one’s homeland, encompassing love for its location, customs, culture, and shared way of life. It is inclusive, defensive, and often critical, allowing for pride in national achievements while acknowledging flaws and striving for improvement. Nationalism, conversely, is more ideological, emphasizing the nation as a political entity—frequently tied to ethnicity, language, or history—and prioritizing its sovereignty, power, and prestige through state mechanisms. This statist bent can lead to aggressive pursuits of dominance, exclusion of outsiders, and uncritical loyalty to the nation-state, regardless of its actions.

A striking historical example of the blending of patriotism and nationalism comes from Benito Mussolini, the founder of fascism in Italy, whose ideology deliberately fused these concepts to consolidate power (Mussolini and Gentile, 1932). Mussolini’s approach weaponized the cultural and emotional pride of patriotism—love for Italian heritage, Roman grandeur, and communal customs—into a tool for nationalist state-building. He absorbed the inclusive, affectionate elements of patriotism and channeled them into an aggressive, statist nationalism that demanded total subordination to the state. This blending was not accidental but a calculated ideological maneuver to mask authoritarianism under the guise of national unity. In his Doctrine of Fascism (1932), co-authored with Giovanni Gentile, Mussolini articulated this fusion: “Everything within the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state” (Mussolini and Gentile, 1932). This quote encapsulates the totalitarian essence, where patriotic sentiment is co-opted to serve the state’s omnipotence, erasing individual autonomy and turning cultural pride into a vehicle for political domination. Fascism, under Mussolini, presented itself as the ultimate expression of national love, but it was nationalism’s power-hungry core that drove policies like imperial expansion and suppression of dissent.

Mussolini’s ideological evolution is particularly revealing, as he came directly from a Marxist standpoint. Born into a socialist family, his father Alessandro was a fervent socialist who blended Marxism with anarchism and nationalism, naming his son after socialist figures. In his youth, Mussolini was an ardent socialist, editing the Italian Socialist Party’s newspaper Avanti! and rising to its National Directorate by 1912. He immersed himself in Marxist literature, quoting extensively from Marx and Engels, and described Karl Marx as “the greatest of all theorists of socialism.” As a young man fleeing to Switzerland in 1902 to avoid military service, Mussolini carried a nickel medallion of Karl Marx in his pocket as a talisman, symbolizing his deep admiration and viewing Marx as possessing “a profound critical intelligence.” Even in a 1932 interview, he reflected on this period: “It was inevitable that I should become a Socialist ultra, a Blanquist, indeed a communist. I carried about a medallion with Marx’s head on it in my pocket.” His expulsion from the Italian Socialist Party in 1914 stemmed from his support for Italy’s entry into World War I, which he believed could spark socialist revolutions across Europe—a heretical view diverging from Marxist internationalism.

This shift from Marxism to fascism was not a complete abandonment but a revisionist adaptation. Mussolini retained Marxist elements like class struggle but reframed them through a national lens, rejecting international proletarian solidarity in favor of national corporatism. He viewed fascism as a “Marxist heresy,” evolving socialism into a state-centric ideology that prioritized national unity over class warfare. Influences like Georges Sorel’s revolutionary syndicalism bridged this gap, emphasizing myths and violence to mobilize masses, which Mussolini fused with nationalist fervor. By the 1920s, his regime glorified the state as the embodiment of the nation’s will, blending patriotic cultural revival (e.g., Roman symbolism) with nationalist aggression (e.g., invasions of Ethiopia). This deliberate dilution of distinctions served to legitimize totalitarianism, presenting fascism as mere “love of country” while enforcing state supremacy.

From an Austrian economics perspective, as articulated by thinkers like Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek, these concepts must be evaluated through the lens of individual liberty, free markets, and wealth creation as the foundation of societal well-being (Mises, 1944; Hayek, 1944). Austrian economists view societal progress not in terms of collective power or equality but as the outcome of voluntary exchanges, entrepreneurship, and the efficient allocation of resources unhindered by state intervention. Wealth creation, in this view, arises from individual actions in a free market, fostering innovation, productivity, and prosperity that benefit society as a whole. Inequality is not inherently problematic; rather, it serves as an incentive for effort and innovation, provided it results from market processes rather than state favoritism or coercion.

Inequality is a slandered concept, just as diversity, and it is important to see that diversity is based on inequality. Humans should embrace inequality as it creates opportunities through specialization, recognizing every individual’s different talents and possible contributions, and that is exactly what makes diversity so important, too: different ideas and opinions enrich our public discourse, our education and upbringing. There is no diversity in mono-culture, be that in the planting of plants and forests, or ideologically slanted oppression of dissents. Understanding the strong and the weak points in other opinions and suggestions is crucial for progress and development, and quota or other ill-informed attempts of enforcement have always failed to provide the same efficiency as simple meritocracy. Therefore: Inequality is per se beneficial, equality per se what nature and evolution avoids at all cost leading to stagnation and decay.

Free markets embrace meritocracy and inequality wholeheartedly. However, free markets are more theoretical as they have never truly been tried because the moment there is a government and legal tender, borders or taxation, regulation or subsidies – the market is not free anymore. At no point has any monarchy, theocracy, democracy or dictatorship ever had a free market because of their interference with some or all of the above points. It is therefore that we say: not only are left and right nothing but parallel movements, both being statist and collectivist and in no way their “opposite”, but also it has historically become evident that all government is ultimately oligarchic, no matter its declared orientation. Oligarchic meaning “the rule of a few”, and whether it is a representative democracy or a dictatorship, it is never one or all, who rule. Delegation is an inevitable part of organization, making every political system ever tried an oligarchy. Anarchy, anarcho-capitalism, capitalism itself, or aparactonomy, have never been tried or realized, while socialism and communism has been tried at least 51 times and failed every single time, and the same is true for its twins fascism and nationalism (all of which has been explained in detail by Reisman, 2005; Zitelmann, 2022; Hoppe, 2001).

Patriotism aligns more closely with Austrian ideals because it emphasizes personal and cultural attachment without necessitating state expansion. It can coexist with free markets, as individuals pursue wealth creation within their cultural context, fostering voluntary cooperation and trade. Nationalism, however, often demands state intervention to assert national superiority, such as tariffs, subsidies, or military expansion, which Austrian economists decry as distortions that stifle wealth creation (Mises, 1944). Mises warned that nationalism’s desire for power leads to protectionism, reducing trade and global efficiency, ultimately harming the nation’s own economy. Hayek critiqued nationalism for fostering collectivism, where the state’s pursuit of “national interests” overrides individual rights, leading to central planning and inefficiencies (Hayek, 1944). Mussolini’s fascism exemplifies the dangers of this blend from an Austrian viewpoint (Zitelmann, 2022). His “state above all” doctrine epitomized collectivism, subordinating markets and individuals to state corporatism, which Reisman and Hoppe critique as a variant of socialism that destroys wealth through interventionism (Reisman, 2005; Hoppe, 2001). Zitelmann highlights how fascist economics mirrored socialist planning, leading to inefficiencies and failure, much like communist regimes (Zitelmann, 2022).

Empirical Advantages and Disadvantages of Patriotism and Nationalism

Both patriotism and nationalism have demonstrated empirical strengths in fostering societal cohesion, which can enhance economic efficiency and wealth creation, but they also carry risks when unchecked. From an Austrian perspective, societal well-being is measured by wealth generation—through free markets, innovation, and voluntary exchange—rather than equality or state power. Wealth, in this view, historically correlates with justice, peace, and environmental solutions, as prosperous societies afford better institutions and technologies. Inequality is beneficial as it incentivizes productivity, while problems like environmental degradation stem from central planning and cronyism, not markets.

Mussolini’s fascist regime provides a case study in nationalism’s advantages and pitfalls (Zitelmann, 2022). Initially, his blend unified Italy post-WWI chaos, fostering cohesion that enabled infrastructure projects and economic recovery in the 1920s. Patriotic appeals to Roman heritage mobilized public support, while nationalist policies like the Battle for Grain boosted self-sufficiency temporarily. However, the statist core—”everything within the state”—led to corporatist controls that distorted markets, inflated bureaucracy, and culminated in economic collapse amid WWII (Mussolini and Gentile, 1932). This mirrors Austrian critiques of nationalism as leading to inefficiency and war.

Advantages of Patriotism

Patriotism’s strength lies in its ability to unite diverse groups around shared values without aggressive statism, promoting economic harmony. Empirically, patriotic sentiments have bridged divides, fostering altruism and civic engagement that support market stability. In the US, patriotism has historically unified immigrants, enabling large-scale economic growth through voluntary labor markets and innovation. Psychological studies show patriotic attitudes enhance group cohesion and creativity, leading to higher productivity. In Iberia, pre-democracy patriotic pride in cultural heritage supported private property and low debt under dictatorships, contributing to safety and economic moments of success. From an Austrian lens, patriotism aligns with Mises’ “liberal nationalism,” encouraging free trade that boosts wealth—e.g., post-WWII reconstructions in Japan, where patriotic rebuilding via markets achieved rapid growth.

However, patriotism’s disadvantages include potential complacency, where uncritical pride ignores inefficiencies and overlooks the strides other cultures made in the meantime. Iberia’s last 500 years exemplify that complacency, as the explorers and conquerors stopped keeping up with building better ships and nautical science, became dependent on colonial gold and labor and ultimately plunged into debt, decadence and irrelevance.

Another severe problem with patriotic emotion and identification is the exclusion of “the others” and the preferential treatment of “us”. This particular weakness is even worse in nationalism.

Advantages of Nationalism

Nationalism excels in mobilizing political action for unity and development. In Norway, economic nationalism protected resources, yielding high living standards. Anti-colonial nationalism, as in India, fostered self-determination and growth. In Iberia, Franco’s nationalism stabilized finances initially, with low inflation and debt. Austrian economists like Mises saw value in nationalism’s role in anti-imperial movements, provided it avoids aggression and embraces trade (Mises, 1944).

Yet, nationalism’s downsides are severe: exclusion and statism distort markets. Aggressive variants lead to wars, reducing wealth—Mises noted nationalism’s power hunger causes protectionism (Mises, 1944). In Iberia, Salazar’s colonial nationalism drained resources, exacerbating slumps. Mussolini’s regime illustrates this: initial cohesion gave way to economic distortion and failure, as Hoppe and Reisman argue fascism, like socialism, inevitably collapses under interventionism (Hoppe, 2001; Reisman, 2005).

Overall, patriotism and nationalism risk cronyism, nepotism and thus tend to limit meritocratic principles. Iberia’s history shows both can aid progress but often devolve into statist traps, and both lack the inclusion of talent that comes with diversity and meritocracy.

Iberia’s Economic Trajectory: From Dictatorships to Democratic Stagnation

Iberia’s economic history since the 1960s reveals a pattern of initial dynamism under authoritarianism, followed by stagnation amid democratization, social democracy, and EU integration. The 1960s “miracles” under Salazar and Franco liberalized economies, attracting investment and boosting GDP (Prados de la Escosura, 2003). Spain’s GDP growth averaged 7.5% from 1961-1973, second only to Japan, with per capita income rising significantly (Prados de la Escosura, 2003). Portugal achieved notable gains before colonial wars reversed them. Private property thrived, debt was low, inflation controlled, and safety high. Home ownership rates were robust.

However, industrial policies triggered rural exoduses, creating urban challenges. Salazar’s colonial wars drained Portugal’s gains. Transitions to democracy introduced social democracies, nationalizations, and welfare expansions, sparking inefficiencies. Public debt soared, inflation rose in the 1980s, and home ownership faltered amid speculation.

EU accession in 1986 initially boosted growth via funds, raising GDP per capita. Yet, dependency bred complacency, inflating bubbles and exacerbating recessions. Recent years saw COVID contractions, energy crises, and sluggish recovery, with forecasts showing modest growth amid high debt and inflation pressures. Since the introduction and usage of the Euro as sole legal tender, Spanish salaries have stayed the same, and have risen too little in Portugal as both countries saw a severe increase in cost of living, housing and education. Both countries slipped, have precarious health systems and collapsing welfare systems, low birthrates, perilous labor shortages and no solutions at all to counter any of these issues. Rising criminality and taxation makes foreign investment questionable as answer either, and neither country did itself any favors by increasing energy costs through the Green Deal rackets the EU offered, only making the Iberian deindustrialization worse and further aggravating the rural exodus. The gap between urban and rural population makes it hard for conservatives to do what would be necessary in the countryside as it decreases their votes in urban areas that demand full focus and subsidies.

Conservative parties mirror and continue left’s errors: high taxes, cronyism, overregulation. EU integration masked deindustrialization, fostering subsidy reliance without promoting innovation and key technologies.

Critique of Socialism/Social Democracy and Conservative Parties

Social democracy in Iberia promised equity but delivered stagnation through redistribution and bureaucracy. From an Austrian view, this central planning breeds cronyism, distorting markets and reducing wealth. Corruption scandals exemplify statist failures.

Conservatives, despite rhetoric, perpetuated schemes. Both sides blame externalities for crises, ignoring regulations stifling supply. EU membership aggravated slumps: subsidies fostered dependency, regulations slowed reforms. Mussolini’s fascism, with its socialist roots, parallels this: state intervention promised progress but delivered decay (Zitelmann, 2022).

The Rise of Chega and Vox: Not Promising Remedies

First and foremost, let’s learn from Germany. The post-WWII Wirtschaftswunder is often attributed to Ludwig Erhard’s conservative, market-oriented policies that were not free market but “Soziale Marktwirtschaft”, meaning social market. However, Germany’s utter destruction created massive pent-up demand, providing unparalleled opportunities for suppliers. Massive US Marshall Plan investments rebuilt Western Germany, benefiting both economies. The short periods under the SPD (socialists) saw dips, but this highlighted socialist shortcomings rather than conservative brilliance. Helmut Kohl’s reunification, heavily pushed by the US under Reagan, imposed heavy costs on the West through redistribution, fueling inflation and straining Bavaria’s engine for decades. Angela Merkel’s “conservative” era brought Energiewende (costly green transition) and open immigration policies, effectively deindustrializing Germany and undermining its social cohesion. By early 2026, under Chancellor Friedrich Merz (elected in May 2025 after CDU/CSU’s February win with ~28.6%), Germany faces rising debt (projections around 65-68% GDP in 2026-2027, with massive borrowing plans including special funds and defense/infrastructure spending) amid slow recovery, illustrating how “conservative” statism repeats interventionist errors. Merz’s policies, possibly influenced by his past ties to BlackRock (where he chaired the supervisory board of the German subsidiary until 2020; Martín, 2025), include plans to raise public debt significantly—potentially by hundreds of billions through special funds and debt brake reforms—to buy more weapons and increase support for the Ukraine war, which would cause further debt, benefiting only BlackRock (partially owning major NATO weapons manufacturers), while having Germans pay the price.

Both Chega and Vox define themselves as conservative, emphasizing patriotism, tight borders, and national priorities. Chega surged to ~22-23% and around 60 seats in the May 2025 election, becoming main opposition (overtaking PS in seats). Vox holds polls at ~15-17% in 2025-2026; no clear EU exit push—they joined the Patriots for Europe group (with Orbán, Le Pen), focusing on sovereignty/reform, not abolition.

Neither clearly advocates EU exit (“Pexit” or “Spexit”), only sporadically mentioning it while pushing for EU reform—a flawed strategy, as the EU embodies central planning—reformed or not—that Austrian economists know to never be able to outperform self-organizing free markets (Hayek, 1944). Chega and Vox rarely reference Austrian thought—that in itself should ring an alarm bell.

The downside of their patriotism—exclusion of “others,” limiting diversity via preferential “us” treatment—is evident in anti-immigration stances and national priorities, foreseeable leading to slower (compared to socialists/greens) but inevitable failure. “Strong governments” invite interference; such is the fate under statism.

Chega and Vox emerged amid frustration. Yet, they retain statism: protectionism, national controls distort markets, failing wealth creation—like Mussolini’s blend led to collapse (Mussolini and Gentile, 1932).

Better than the current establishment? Sure. A long term solution? Sure not.

Chega and Vox are the lesser evil, offering short term improvements without the long term consolidation that requires abolishing bureaucracy and central banking to ensure the 3 essential human rights: life, liberty and property.

Aparactonomy: Iberia’s Best Solution – The Stateless Nation

Aparactonomy, very similar to anarcho-capitalism, differs in a crucial detail: it promotes the stateless nation, utilizing the unifying and empowering advantages of nationalist and patriotic identification without compromising diversity (Hoppe, 2001). Hoppe’s private law society is the way to go but to make it feasible and acceptable aparactonomy focuses on the stateless nation with strong borders and elite defense. Where no state interferes, diversity is bound to prosper, hand in hand with patriotism. There is nothing wrong with borders, as they clearly mark a property that has to be defended, on all levels. A strong nation doesn’t invite the corrupt elements of other societies and their psychopathic outgrowths; a strong nation is heavily armed just like every single household within that nation. A nation is a culture and its borders, not a color of skin or a linguistic variant with army and navy to tax its citizens. In an aparactonomous society military and police are private, elite and ever adaptive; they improve the way all private enterprise do by embracing the pressure of market mechanisms and the consequential need for fast adaptation through R&D. Monopolies are best evaded through zero regulations, as those are the very foundation of monopoly formation.

Empirically, stateless models succeed: Jewish diaspora networks drove innovation via culture and overseas Chinese kinship boosted trade. Switzerland’s limited central authority yields prosperity via autonomy.

Iberia would prosper fast by allowing and devolving power to its regions, promoting not just Portuguese or Spanish but even pan-Iberian cultural initiatives. Such steps will reduce inefficiencies, boost entrepreneurship, and leverage diversity. Unlike Chega/Vox statism or EU kleptocracy, aparactonomy promotes the preservation of patriotic culture without nationalist aggression, socialist redistribution or centralist planning.

In conclusion, Iberia’s slump roots in statism—left, right, or bureaucratically blended and transcended. Aparactonomy offers revival through market freedom, cultural unity and intertwined diversity. Nationalism, the double-edged sword, statism, the Damocles’ sword over Europe’s wealth and economic self reliance, and socialism the deadly sword hidden behind the mask of morality and social justice, must all be sheathed, for good.

References

Hayek, F.A. (1944). The Road to Serfdom. London: Routledge.

Hoppe, H.-H. (2001). Democracy: The God That Failed. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Kayser, K.H. (2025). Aparactonomy. DeSci Labs. https://doi.org/10.62891/39006333

Martín, F. (2025). German Chancellor Merz’s US ex-employer, BlackRock, will benefit most from ReArm Europe. CADTM. https://www.cadtm.org/German-Chancellor-Merz-s-US-ex-employer-BlackRock-will-benefit-most-from-ReArm

Mises, L. von (1944). Omnipotent Government: The Rise of the Total State and Total War. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Mussolini, B. and Gentile, G. (1932). The Doctrine of Fascism. Florence: Vallecchi.

Prados de la Escosura, L. (2003). El progreso económico de España, 1850-2000. Madrid: Fundación BBVA.

Reisman, G. (2005). Why Nazism Was Socialism and Why Socialism Is Totalitarian. Laguna Hills: The Jefferson School of Philosophy, Economics, and Psychology.

Zitelmann, R. (2022). Hitler’s National Socialism. London: Management Books 2000.